Intrahepatic arterial-portal fistulas are well known and are usually secondary to trauma on liver biopsy. Conversely, portahepatic fistulas are name and seem to be congenital; only three cases have been reported in the literature, to our knowledge. We present what we consider to be the first case that has been surgically corrected.

CASE REPORTS

Case 2.-A 74-year-old woman was seen because of intermittent episodes of dysarthria for 6 years. There was no history of abdominal surgery, liver biopsy, trauma, or alcohol abuse. Physical examination showed bilateral cere-bellar and pyramidal tract signs, with astenixis but no hepatosplenomegaly. Venous blood ammonia was elevated fivefold; laboratory test results were otherwise negative on normal. Endoscopy

failed to show any esophageal varices.

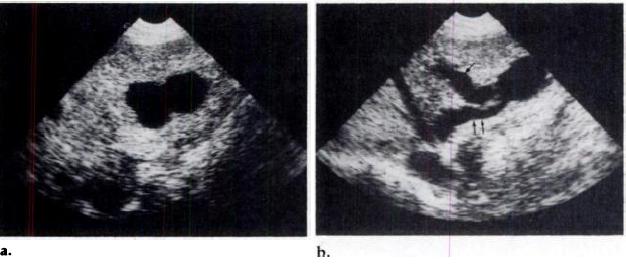

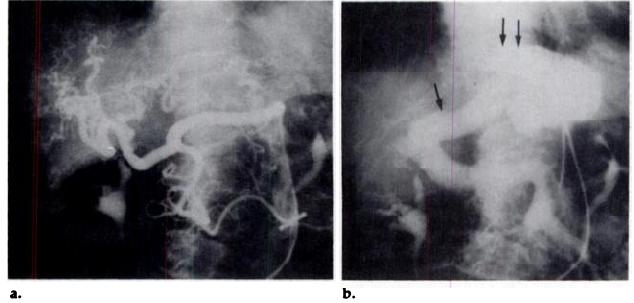

Ultrasound (US) examination (Fig.la, ib) showed a bilocular aneurysm in the lateral segment of the left hepatic lobe; it communicated with the left portal vein and the left hepatic vein. The hepatic artery was also dilated. Celio-mesentenic angiognaphy (Fig.2a, 2b) confirmed these findings and also showed poor opacification of theright portal vein. Percutaneous aneurysmal occlusion using a 27-mm balloon

at the junction of the fistula and the left hepatic vein was unsuccessful because of the great size of the malfonmation; contrast medium injected through this balloon still reached the dilated hepatic vein. Neither a balloon non a coil was released in the fistula because of the high possibility of dislodgment

toward the inferior venacava.

Figure 1. Case 1. Transverse sonograms demonstrate biloculate aneurysm (a) in the

lateral segment of the left hepatic lobe. It communicates with the left portal vein (single

arrow) and the left hepatic vein (double arrows) (b).

Figure 2. Case 1. Celio-mesentenic angiognaphy shows dilatation of the hepatic antery

and its tortuous branches (a); in the venous phase (b), the dilated left portal vein

(single arrow) feeds the fistula, which also communicates with the dilated left hepatic

vein (double arrows).

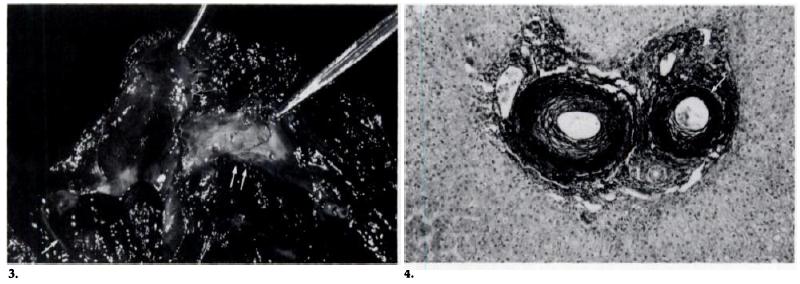

The liver biopsy was normal preopenatively, without any cirrhosis. Duning surgery, pressures in the right and left portal veins were normal (6-10mmHg); the pressure in the right pontal vein increased slightly (16-21 mmHg) after temporary occlusion of the left portal vein, its infenolatenal segmental branch, or even the left hepatic vein. The surgeon considered the portal pressure increase moderate and

resected the lateral segments of the left hepatic lobe. Macroscopic examination of the opened lateral segment of the left lobe (Fig. 3) confirmed the presence of a portahepatic venous fistula that contained clots. Microscopic examination of portal spaces demonstrated abnormal muscular hyperplasia of the ranches of the portal vein and dilatation of the branches of the hepatic vein; some portal spaces displayed huge, dystrophic, tortuous branches of the hepatic artery, the walls of which contained numerous elastic fibers (Fig.4). The postoperative outcome included an episode of encephalopathy with

a grade 1-2 coma; our patient recovened from the encephalopathy in 15 days and her serum ammonia levels

returned to normal and EEC abnonmalities improved. Endoscopy nevealed slight esophageal vanices. One

year later, the patient had no encephalopathic signs except those of a moderate cerebellar syndrome.

Case 2.-A 63-year-old woman was admitted because of hypoglycemic attacks; she denied prior abdominal sungery,trauma, or alcohol abuse. The physical examination was normal, and there were no neunologic signs, abdominal bruits, on signs of encephalopathy. Except for sulfobnomophthalein extraction (Bromsulphalein [BSP] Sodium; Hynson, Westcott, and Dunning; Baltimore), the liver function tests were normal. The venous blood ammonia level was elevated twofold, and there was impaired glucose tolerance

with poststimulative hypoglycemia secondary to persistent hypeninsulinemia and lowering of the C

peptide/insulin ratio.

Figures 3, 4. Case 1. (3) Macroscopic view of the opened lateral segment of the left lobe confirms the presence of a fistula (singlearrow) that contains clots and communicates with the left portal (double arrows) and hepatic (triple arrows) veins. (4) Microscopicview of portal space displays huge, dystrophic, tortuous arterial branches (arrows), the walls of which contain numerous elastic fibers.

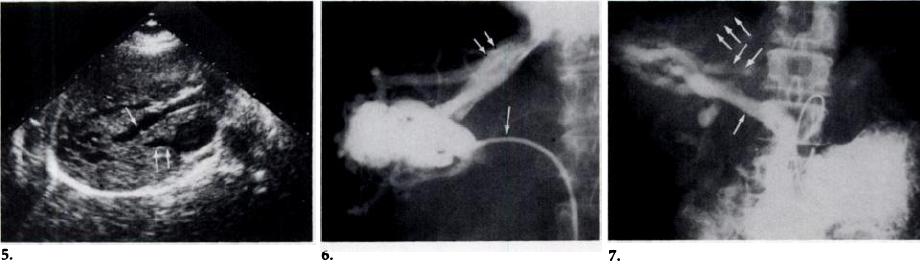

Figures 5-7. Case 2. (5) Transverse sonogram demonstrates a complex of branched venous channels within the posterior segmentof the night lobe of the liven; this malformation communicates with the night portal vein (single arrow) and with a right accessoryhepatic vein (double arrows). (6) Hepatic venognam obtained after injection of contrast medium in the accessory hepatic vein(single arrow) shows opacification of the venous malformation, right hepatic vein (double arrows) and the vena cava. (7) Venous phase of the mesentenic angiography demonstrates the right portal vein (arrow) feeding the fistula that flows into the accessory(double arrows) and right hepatic (triple arrows) veins.

Sonograms (Fig. 5) demonstrated a complex of branched venous channels within the posterior segment of the night lobe of the liver; this malformation communicated with the right portal vein and with a night accessory hepatic vein that joined the inferior vena cava under the confluence of the three hepatic veins. The hepatic venognam (Fig. 6) revealed normal free pressure measurements. Injection of contrast

medium in the accessory hepatic vein opacified the venous malformation, the night hepatic vein, and the inferior vena cava. The venous phase of mesentenic angiognaphy (Fig. 7) demonstnated the night portal vein feeding the malformation, which flowed into the accessory and the night hepatic veins. Simple dietetic treatment nelieved the hypoglycemic symptoms of this patient.

DISCUSSION

Our review of the literature mevealed documentation of only three cases of pontahepatic venous fistulassimilar to the two reported here; none of the three were evaluated using US (1-3). Congenital extrahepatic portacaval shunts are also rare (4). Pediatric portacaval shunts, which are always associated with many other malformations, have also been described. Finally, various articles

have been published on the intrahepatic or extrahepatic venous malfommations (2, 5-7). We have identified the common patterns between our two cases and the three we have found in the literature

(1-3). Anatomically, pontahepatic venous fistulas are more often located in the might lobe. They can

be fed by the right or left portal vein and can flow into any hepatic vein depending on their location in the liver.

Pontahepatic aneurysms are congenital: none of the patients had any history of abdominal trauma, sungery, or liver biopsy, and only one(3) had portal hypertension. The aneurysms are anatomically different from sinusoidal

典型病例分享

典型病例分享