HISTORY

A 72-year-old black woman had a history of abdominal pain,diarrhea, and weight loss of approximately 4 months duration at presentation to her primary care physician. The pain was initially episodic and did not localize to a specific quadrant. In the 4 weeks prior to presentation, cramps and abdominal pain were associated with meals and were relieved after a bowel movement. She did not have a fever or the chills. Her medical history included recurrent right-sided headaches, partial loss of vision in the right eye, anemia, and peripheral vascular disease for which she underwent bypass graft surgery. At physical examination, there was no marked abdominal tenderness and there were no peritoneal signs of disease. Bowel sounds were normal. Laboratory values were normal, and tests for rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies were negative. Findings of an initial small bowel series did not suggest any abnormalities. The patient had an abnormal angiogram that was obtained at another institution, and findings reportedly suggested diffuse arterial abnormalities (ie, abnormalities of the temporal, iliac, renal, and mesenteric arteries). The patient had worsening signs of bowel ischemia, and bypass surgery

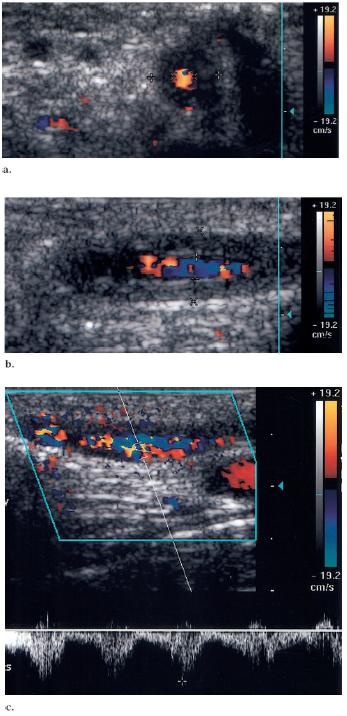

was performed to treat a distal superior mesenteric artery (SMA) occlusion. Intraoperative color and spectral Doppler ultrasonography (US) was requested to examine the aorta and visceral vessels for evidence of stenosis or occlusion during bypass surgery performed in the SMA. Transverse (Fig 1a) and longitudinal (Fig 1b) images of the SMA are shown. Color and spectral Doppler US was performed to characterize the degree and extent of SMA stenosis. Visualization of an optimal nonstenotic segment of SMA for bypass surgery was desired. Examination of the celiac artery did not disclose any abnormalities.

The inferior mesenteric artery was not examined with US.

IMAGING FINDINGS

An intraoperative US image of the SMA showed the vessel and demonstrated flow within the vessel lumen. The SMA was patent, but the lumen was markedly narrowed and was no more than 1.7 mm in diameter (Fig 1). The SMA was nearly occluded at the division of the SMA into its branches at US. A thick circumferential hypoechoic wall or “halo” was seen. The hypoechoic wall thickening was diffuse and symmetric. There was no displacement of the vessel because of a mass. No focal aneurysms were identified in the proximal portion of the vessel. At spectral Doppler US (Fig 1c), turbulent flow was demonstrated. Computed tomography (CT) was performed after a bypass graft of the iliac artery to the SMA was successfully placed. On the CT scan, the proximal SMA wall was concentrically thickened (Fig 2a). There was distal focal occlusion of the SMA (Fig 2b). The bypass graft of the iliac artery to the SMA entered the SMA several centimeters distal to this occlusion.

Figure 1. Representative intraoperative (a) transverse and (b) longitudinal

color Doppler US images of the SMA. Diffuse symmetric hypoechoic

halo (cursors) surrounds the patent lumen. The vessel is narrowed

and is 1.3–1.7 mm in diameter. (c) Longitudinal color spectral

Doppler US image of the SMA demonstrates turbulent flow. US image

demonstrates aliasing and disturbed flow within the vessel.

Figure 2. (a,b) Selected transverse images obtained at contrast material–enhanced helical CT

demonstrate concentric thickening (arrows) of the SMA seen on a, with occlusion (arrows)

observed on b, a more caudal image.

DISCUSSION

This patient had bowel ischemia and a history of unilateral headaches and vision loss at presentation. Concentric hypoechoic thickening of the SMA wall was seen at intraoperative US. The differential diagnosis included vasculitis, atherosclerosis, and malignant involvement of the vessel. The US findings

and the clinical history are most consistent with a type of vasculitis, most likely giant cell arteritis. Giant cell arteritis is the most common primary systemic vasculitis and typically affects those who, such as this patient, are older than 50 years of age. There are two common constellations of findings in giant cell arteritis: temporal arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica. Symptoms of temporal arteritis include unilateral headache, facial pain, jaw claudication, or loss of vision. Temporal arteritis is a common manifestation of giant cell arteritis and may be confirmed by using temporal artery biopsy (1). Histologic analysis may reveal granulomatous inflammatory changes. A temporal artery biopsy in this patient demonstrated giant cells and chronic inflammatory changes in the temporal artery, findings that are consistent with temporal arteritis. In many patients, the clinical manifestation and laboratory values are suggestive of a diagnosis of temporal arteritis and a biopsy is unnecessary. However, in cases of clinical uncertainty, biopsy may be required for a definitive diagnosis.

A characteristic gray-scale US finding of giant cell arteritis involvement of the temporal artery is a diffusely thickened hypoechoic arterial wall or halo. Color and spectral Doppler US may depict turbulent flow and stenosis of the affected vessel. Schmidt (2) states that the halo must be circumferential and must be demonstrated in two planes. In his large series, the sensitivity and specificity of a halo and stenosis detection by using duplex US to diagnose giant cell arteritis were 71% (n � 56) and 99% (n � 364), respectively, on the basis of a clinical diagnosis of giant cell arteritis or 80% (n � 39) and 91%

(n � 47), respectively, on the basis of a histologic diagnosis. In his series, only two of 364 patients with a clinical diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica had the halo in a patent temporal artery and had histologic findings negative for giant cell arteritis of the temporal artery (2). There is some debate about whether the combination of gray-scale and color Doppler US findings is specific enough to replace biopsy for the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis (3).

Extracranial vessel involvement is not an uncommon finding in patients with temporal arteritis at autopsy, although clinical manifestation due to the effects of the extracranial vessel involvement is rare (4). Large-vessel involvement, especially that of the extremities, has been described, including the brachiocephalic artery and carotid artery (5). A halo, similar to that observed in our case, has been described in the axillary and brachial arteries. The hypoechoic halo in these vessels became hyperechoic within 1 year after treatment. It is hypothesized that this was due to resolution of acute edema and development of sclerosis, fibrous intimal hyperplasia, scarred media of the vessel wall, and fibrosis. Mild thickening, as well as subtotal occlusions, of the brachial and subclavian arteries has been reported (5). In an article by Schmidt et al (6), an interesting note was the resolution of the halo in a mean of 16 days after the commencement of corticosteroid therapy. Since the SMA is an unusual location for giant cell arteritis, other vasculitides should also be considered in the differential diagnosis. The SMA may be involved in large-vessel vasculitides, such as Takayasu arteritis or giant cell arteritis. Mediumvessel vasculitides, such as polyarte

典型病例分享

典型病例分享